Harrow and Hillingdon Geological Society

Geology of London

Home | Monthly Meetings | Field Trips | Exhibitions | Other Activities | Members Pages | Useful Links

Beneath our feet: the geology of London

Diana Clements

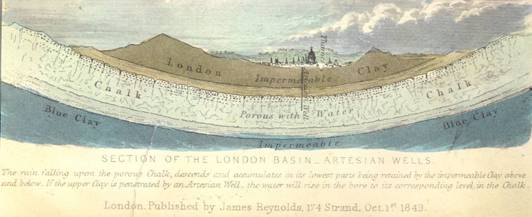

As part of the background to this talk, Diana explained that she had been asked by the Islington Museum to help with an exhibit on The geology of Islington and had produced a booklet to accompany it. She was also editor of the Geologists’ Association Field guide to the geology of London, when she obtained relevant contributions from those who knew the sites best and did much of the writing to support those contributions. She followed this up with a submission of additional potential sites to the draft of London’s foundations, a geodiversity audit of 36 sites, which was funded by the Greater London Authority and published in 2009. Since then she has been an active member of the London Geodiversity Partnership in guiding the production of its Geodiversity Action Plan and its implementation. Clearly useful also is the British Geological Survey Memoir on The geology of London. The geology of the London Basin has long been known, with the Terrace gravels underlain by London Clay, Lambeth Group, Thanet Sands and Chalk and an 1849 section shows the form of this to illustrate the source of water in London from the Chalk supplying, for example, an artesian well in Trafalgar Square.

Section across the London Basin drawn in 1849, highlighting where London gets its water

The talk covered 4 areas:

1. The geology of London;

2. The structure of London;

3. What can we see and where?

4. How can we protect geodiversity and make the best use of it?

Geology of London

Mylne’s map of the geology of London was produced at a time when much of the geology could still be seen because quarries such as Gilbert’s Pit in Charlton were still active. Whittaker in 1899 described railway cutting sections, which are now largely obscured.

Harefield Quarry when operating in 1914

Solid strata in the centre of London comprise the London Clay, sandwiched by the Lambeth Group, Thanet Sands and Chalk, with the youngest strata being the Bagshot Sands in the middle of the London Basin syncline, which is of Alpine age. Superficial deposits comprise the Thames terraces and earlier terraces related to the proto-Thames, with Anglian till in Epping and Finchley.

Pre-Anglian gravels were deposited by the proto-Thames, when it flowed north of London through St Albans to Clacton, and by the southern tributaries, which flowed across the London Basin to join the proto-Thames. The Anglian ice sheet (450,000 years ago) came down the Colne Valley and down to Hornchurch and Finchley. Great lakes formed in front of the ice and the Moor Mill Lake in the Colne valley overflowed and diverted the Thames to its present valley. After the Anglian glaciation, there are a series of terraces with typical mammal assemblages, such as the hippopotamus found in Trafalgar Square. The 1:10,000 maps of the Geological Survey of Great Britain, published in 1920, are particularly useful in showing the lost rivers and a mass of borehole data. The lowest terrace is the Kempton Park gravel.

Evidence for dating in the Quaternary includes elevation, the higher the terrace the older it is, as well as the fossil assemblages. The till includes derived Jurassic fossils and chalk. The Swanscombe skull was found in 3 separate pieces in the oldest of the terraces but elsewhere there are no human remains, though there are plenty of hand axes and animal bones. At King’s Cross (Battlebridge), a hand axe and elephant molar were found together as long ago as the 17th century.

The youngest solid rock is the Bagshot Formation and there is a 40 million-year depositional gap above it to the Quaternary. Below that are the Claygate Beds and London Clay (together comprising the London Clay Formation), the Harwich Formation and the Woolwich, Reading and Upnor Formations of the Lambeth Group, and below these, the Thanet Sand Formation. Most of the surface rocks are Eocene in age.

In London Clay times, there were mangrove forests with nipa palms and magnolia on nearby land, though London itself was under the sea and this material was washed in. Fauna included nautiloids, turtles, fish, sharks and other molluscs. Chris King recognised 5 separate zones in the London Clay, though the BGS have altered the boundaries in the latest memoir.

The Harwich Formation is a mish-mash of fairly deep-water clay with ashbands in the Harwich area derived from the volcanic activity in the Western Isles and Northern Ireland. Closer to London it has shells and pebbles, such as the Blackheath Pebble Bed. The Tilehurst and Swanscombe Members can be seen at Harefield. At Abbey Wood, the sands below the pebble bed contain mammal bones and hooves of tiny horses.

The Lambeth Group includes marine, terrestrial and estuarine deposits in the Upnor, Woolwich and Reading Formations. Sea level went up and down during the Lambeth Group and in the London Basin, following deposition of the glauconitic sands of the Upnor Formation, which is entirely marine, the Reading Beds, of terrestrial origin, interdigitate with the brackish sediments of the Woolwich Beds.

The Thanet Sand Formation ranges from 30m in thickness in the east to zero in the north-west and is of marine origin. There is then a 25 million-year hiatus down to the top of the Chalk in the London area. Denmark has rocks spanning the Cretaceous – Tertiary boundary and Chalk extends right up to the Danian. The full extent of the Chalk and early Danian is also thought to have been present in the southeast England on the basis of Danian derived fossils but before the Thanet Sands were laid down the uppermost parts of the Chalk and any Danian rocks were eroded away.

Chalk is still the most important source of water. It was deposited in warm seas that were reasonably shallow with CaCO3 deposition and high CO2 levels in the atmosphere. It is formed mainly of broken plates of coccolithospheres and macrofauna includes echinoids, sponges, ammonites and corals.

Structure of London

The axis of the London Basin follows the course of the proto-Thames. In Kentish Town, a borehole was sunk for water by the New River Co. and it found Gault Clay below the Chalk and beneath that a hard clay of indeterminate age. A borehole at Tottenham Court Road in 1859 hit Jurassic material before the hard clay, implying faulting. Fossils found in the hard clay proved it to be Devonian in age. The London Basin syncline is imposed on an earlier anticline. Gravity maps show a high in north-west London and a low in Croydon. The basin sits on the edge of the Avalonian craton (the Midlands micro-craton) with the Variscan fold belt to the south.

Old structures continue to influence topography and land movement continues. For example, Northolt is rising at about 0.5mm per year and east London is sinking.

What can we see?

The map of sites considered for London’s foundations shows lots of potential sites in south Hillingdon. The Hornchurch SSSI in a railway cutting has recently been cleared by Railtrack and shows till with the Black Park Gravel (the lowest Thames terrace gravel) on top. Till with derived Jurassic fossils can also be seen in newly excavated graves in Finchley cemetery. A Neolithic submerged forest can be seen on the foreshore at Erith.

Stanmore Gravel at Harrow Weald SSSI

Anglian Till & Black Park Gravel atHornchurch Railway Cutting SSSI.

The Bagshot Beds, the youngest Tertiary rocks, can be seen on top of Hampstead Heath. On the Thames foreshore at Isleworth is London Clay with Eocene molluscs and gastropods and septarian nodules. The Harwich Formation can be seen at Charlton and Abbey Wood, the Woolwich Beds at Gilbert’s Pit and the Reading Beds at Harefield and Pinner Chalk mine, where there is one of the few in situ exposures of the cemented version, the Hertfordshire Puddingstone in the walls of the shaft. Thanet Sands are best exposed in a disused pit (Klinger) next to Tesco’s in Sidcup. The best place to see the Chalk is Riddlesdown, which is owned by the City of London Corporation and very well maintained. Chalk can also be seen at the Chislehurst caves, Harefield, Pinner Chalk mine (if access can be obtained) and on the Chafford Hundred Geowalk.

Lambeth Group at Harefield SSSI

Lambeth Group at Gilbert’s Pit SSSI

Riddlesdown Chalk Quarry

Pinner Chalk mine

How can we protect what remains?

The Greater London Authority and Natural England put money and effort into the assessment exercise that produced London’s foundations and this was taken forward by the London Geodiversity Partnership, which produced an Action Plan covering the needs of these sites and the build environment including museums, exhibitions and building stone walks. London’s foundations is currently being revised for publication as a web document by the GLA. The Partnership is working to obtain formal recognition of Regionally and Locally Important Geological Sites (RIGS and LIGS) identified in London’s foundations and by further assessment by members of the Partnership. We need to work with owners, geological groups and others to conserve sites. Priorities for conservation action have been identified in the SSSIs at Gilbert’s Pit and Harefield.

Work is also being done on interpretation, including the Green Chain Geowalk, with the launch walk on 17 March 2012, and Building London with its links to walks etc. and we succeeded in getting temporary notice boards erected about the geology on Hampstead Heath. This is a small beginning and we hope to work with other groups in the London area to bring geology to a wider audience.