Harrow and Hillingdon Geological Society

The Wallbrook

Home | Monthly Meetings | Field Trips | Exhibitions | Other Activities | Members Pages | Useful Links

The Walbrook, the City of London’s river: its rise and fall

Stephen Myers

Introduction

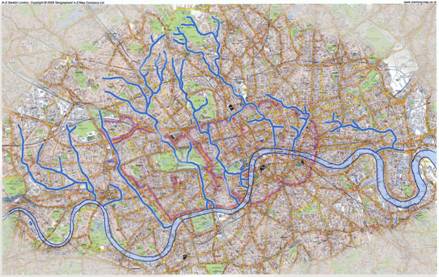

The speaker explained that he was a water engineer, not a geologist but geology had played a significant part in his research into London’s lost rivers, which led to the publication in 2011 of his book Walking on water: London’s hidden rivers revealed. This covered only the rivers on the north bank of the Thames, since many of those on the south bank remain open. From east to west these are the Black Ditch and the Walbrook, 3 rivers rising on Hampstead Heath – the Fleet, Tyburn and Westbourne – Counters Creek, Parr’s Ditch and Stamford Brook.

London’s Hidden Rivers – Thames North Bank

While the Thames is clearly London’s river, the Walbrook is the City of London’s river, flowing right through the centre of the city. For thousands of years before settlement, it flowed as a pristine stream through open country and it was a factor in the Romans’ location of Londinium. Looking across the Thames from the marshes on the south bank, they would have seen 2 low hills (Cornhill and Ludgate Hill) rising above the north bank marshes with the river running between. The Walbrook initially provided the water supply to Roman London as the tidal nature of the Thames meant it was too saline for a drinking water supply. However, the Romans rapidly realised that the gravel superficial deposits were a safer source of drinking water and the Walbrook was used for this purpose for only a short period. The speaker’s particular interest in the Walbrook was in how it affected Roman London.

The presentation covered:

- the Walbrook as it was known and as it is now known;

- how the true extent of the Walbrook and its catchment were determined;

- the fundamental importance of geology to Walbrook research;

- the urban Roman Walbrook’s base flow and storm flows; and

- the impact of the Walbrook’s flow on Roman London.

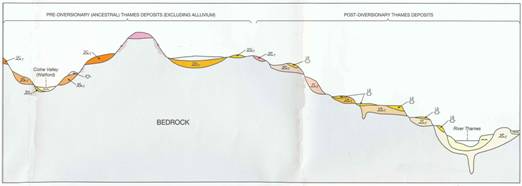

Geology of London’s hidden rivers

The bedrock of London north of the Thames is a thick layer of London Clay, at depth beneath which is the Chalk, and which is capped at Hampstead Heath and Highgate by the Bagshot Sands. Superficial deposits on top of this are, in the Colne Valley, the pre-diversionary or ancestral Thames terrace gravels and in the Thames valley the post-diversionary terrace gravels. In the Walbrook catchment these are, in descending order the Boyn Hill, Finsbury, Hackney and Taplow Gravels and the Langley Silt, a sandy clay and silt, known as brickearth. There is seepage at the interface of the Bagshot Sands and the London Clay (which gives rise to the Fleet, Tyburn and Westbourne rivers) and at the gravel clay interfaces, resulting in springs throughout the Walbrook catchment.

Geological section from the Thames to Watford

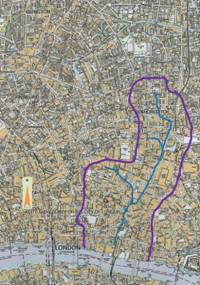

The Walbrook as it was known

Until 3 years ago, we thought we knew the extent of the Walbrook and its catchment. It was thought to rise in Shoreditch (at Hoxton Square), be fed by an artesian well at Holywell ( Curtain Road), pass through the Roman City Wall at London Wall/Blomberg Square and flow into the Thames (then located along Upper Thames Street) at Cannon Street. It was thought to be less than 2km in length but, for such a short river, there appeared to be a surprising extent of flooding in archaeological deposits.

The speaker carried out research for his book in 2009 and 2010 and began his PhD research into the Walbrook in the Roman period in 2010, with submission due in 2015.

The River Walbrook As previously known and As researched for the speaker’s book and PhD

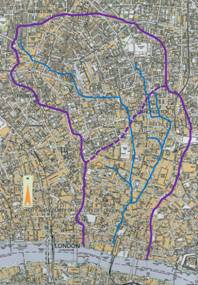

The Walbrook as it is now known

As a result of the speaker’s research, the Walbrook is now known to be a much longer river, with 2 main branches, and larger catchment. Lying between the Fleet and Hackney Brook catchments, the research uncovered a second, western branch, which ran from the Angel Islington past Moorfields, then turned south along Moorgate to meet the easterly branch at London City Wall. There is archaeological, literary and pictorial evidence for the newly discovered westerly branch. However, since 1600, no maps have shown the westerly branch. The easterly branch has also been shown to extend farther north into Shoreditch than previously thought. The westerly branch had its origins in the springs, wells and ponds at the base of the Boyn Hill Gravel and the easterly branch from springs at the base of the Hackney Gravel in a marsh at Hoxton, with tributary flow from Holywell. The two branches are separated by a low ridge and the marsh at Moorfields formed from the waters of the westerly branch and was drained by the easterly branch. The north-west to south-east slope on the gravel – clay interface means that the gravel groundwater catchment extends further north-west than the topographical catchment.

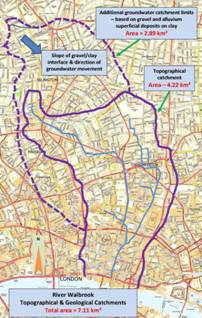

It is still not a big river and not a big catchment. The statistics relating to its size as given in the talk have yet to be accurately determined and were as follows. The topographical catchment covers 422Ha (4.22km 2), predominantly underlain by gravels, with about 5% each of Langley Silt, London Clay and alluvium. The groundwater catchment covers 711Ha (7.11km 2) and is underlain over 70% of its area by gravels, 17% by Langley Silt, 10% by London Clay and 3% by alluvium.

The Walbrook catchment

The catchment was mapped from contour maps and by walking the catchment watershed many times. The route of a continuous drainage channel can still be traced from Old Street to above the angel Islington. 2 basic questions arise:

- Was the source of water above the Angel Islington sufficient to generate perennial flow?

- If so, why was the westerly branch not shown on maps?

How and why did the Walbrook disappear?

In some way, the westerly branch of the Walbrook was erased from public consciousness – but why?

The factual evidence is based upon the extent of the physical catchment, its geology, the remains of a watercourse visible on the ground today, together with evidence from an ancient map of about 1430 and 2 literary sources:

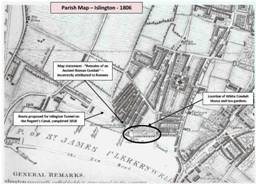

In 1371, Sir Walter de Mauny, bought land to the immediate north of Smithfield from St Bartholomew’s and established a Carthusian Priory (Charterhouse). The land had been previously used to bury 10 – 15,000 victims of the Black Death in 1349. By the late 1420s, water supply to the Carthusian priory was considered contaminated, probably in no small part due to its site on the burial ground, and an alternative supply was sought. St Bartholomew’s Priory at Canonbury had laid a gravity pipeline to supply water to its priory at Smithfield and the success of this led to Charterhouse seeking its own remote supply.

Land was bought at the source of the Walbrook and the waters were collected from the general area of springs and wells straddling the Fleet/Walbrook catchment boundary and taken to the White Conduit, in the Fleet catchment and piped from there to the Charterhouse priory. From then on, the source waters of the Walbrook were diverted. Although Charterhouse stopped using this water when the New River was built in the 1600s, the water still flows down the pipeline today.

There is, therefore, strong evidence that Charterhouse “hijacked” the headwaters of the Walbrook

The circumstantial evidence of the date of its disappearance relates to the marsh at Moorfields.

When the Roman city wall was built across the river it was not bridged but culverts were constructed for the river to flow through, probably with sluice gates to control flooding in Roman London. This partial dam caused Moorfields to flood. With the departure of the Romans in 409AD, London within the walls was abandoned until the 9 th century. The sluices were not maintained, the wall acted as an even more effective dam and Moorfields remained flooded for 1,200 years. Then, suddenly, in the first half of the 15 th century, Moorfield began to dry out. In this period, for the first time, the Roman wall was breached at Moorgate. It appears that the hijacking of the headwaters of the Walbrook by Charterhouse Priory and their diversion into the Fleet catchment resulted in the drying out of Moorfields.

The speaker considered that the prime suspect for hijacking the Walbrook, Charterhouse priory was “guilty as charged”. The maps do not show the westerly branch of the Walbrook after 1430 because it no longer existed.

The Roman Walbrook

The true size of the catchment and the length of the river are important because:

- the size, geology and landscape of the catchment, coupled with rainfall patterns dictates the base flow of the river and its flow at times of high rainfall and storms;

- a reliable base flow would have determined the extent and type of use the Romans made of the river’s waters;

- storm flows and the river’s flow capacity determine flood risk to urban Roman London

The research has estimated base and storm flows, which indicate that the river had sufficient flow to be put to many beneficial uses but also that it would frequently have flooded the flatter areas of urban Roman London.

Were there Roman water mills on the Walbrook?

The precise location of the junction of the easterly and westerly branches of the Walbrook is somewhat uncertain. It could have been north of the Roman wall via Finsbury Circus, rather than south of the wall. Mean high water spring tides in Roman times was at +1.5mOD (compared to +4.0mOD today) and a flow of 60-80L/sec, combined with the fall of 6m from the Roman wall to the Bucklersbury/Lothbury area, would have been sufficient to drive 2 water mills in series, each of 2hp capacity, capable of producing 1.25tonnes of flour per day. The use of water mills to grind grain was common practice in the Roman Empire before they came to Britain.

Results from the archaeological investigation of the Bucklersbury/Bloomberg Square development site may confirm that there were indeed Roman water mills. These excavations found a substantial building, large millstones, a paddle from a water wheel and timber gear.

Conclusions

The speaker concluded that:

- the Walbrook and its catchment are much more extensive than previously thought;

- the hijack of its headwaters in the early 15th century meant its upper reaches disappeared from public consciousness;

- its hijacking led to the drying out of Moorfields;

- its potential for beneficial use, e.g. milling, in Roman times is now better known;

- the risk of it flooding the Walbrook valley in Roman London has been assessed;

- his 5-year research on the Walbrook and Roman London is ongoing – thesis due October 2015; and

- without some knowledge of the geology of the Walbrook catchment, the research into the westerly branch of the Walbrook would not have been triggered.

Addendum on the potential for resurrection of London’s hidden rivers

London’s hidden rivers are now an integral part of the capital’s drainage and sewerage system but what a wonderful amenity they would have provided if they had been protected from pollution. The question arises as to whether they could be revived. Unfortunately the answer is almost certainly no, at least not directly, but there is an example in north London, which shows how they might be restored. At New River Head, a 750m stretch of the New River was left uncovered as a simple concrete channel and the London Borough of Islington has now created a new “ Riverside walk” at Douglas Road, Canonbury, which is both attractive and well used.

The speaker’s suggestion is to revive the Fleet River by collecting water as it overflows from the last of the Highgate ponds and at the junction of the overflow from the last Hampstead pond with the flow from Hampstead and use that water to recreate lengths of river in re-development sites and to feed the lakes in Regent’s Park, Hyde Park and St James’ Park, rather than pumping from the aquifer as at present.

The potential benefits from such a scheme would include the possibility of greening new development in Camden and Westminster by introducing stretches of river, refreshing the lakes in the Royal Parks, lowering the water table locally in Hampstead, th8us easing basement flooding, assist in reducing the urban flood risk from the Hampstead and Highgate ponds and provide top-up water to the Regent’s Canal.

The estimated cost, on a conservative basis, would be £30M and the next step that needs to be taken is a feasibility report.